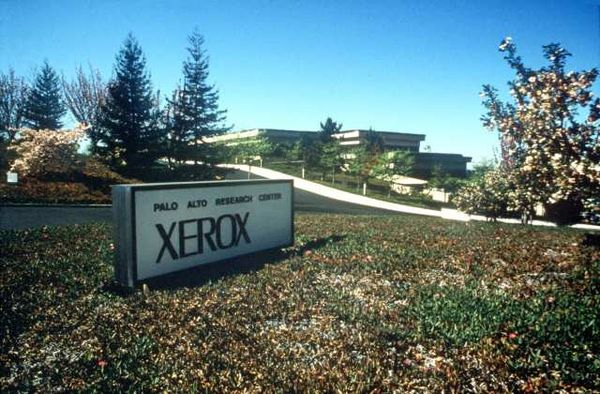

In December of 1979, a 24-year-old Steve Jobs walked into a bland office building in Palo Alto, California. The space didn’t look like much — it had the same beige carpets, fluorescent lights, and boxy terminals as any other tech company. But this wasn’t just any tech company. This was Xerox PARC — the Palo Alto Research Center — a skunkworks division of Xerox Corporation, quietly working on the kind of ideas that sound like science fiction until they don’t.

Jobs had arranged for a private demo. Xerox had invested in Apple earlier that year, and as part of that deal, Apple engineers were given a look at some of Xerox’s most experimental technology. For Xerox, it was a gesture. For Jobs, it was a moment that would reshape his entire understanding of what a computer could be.

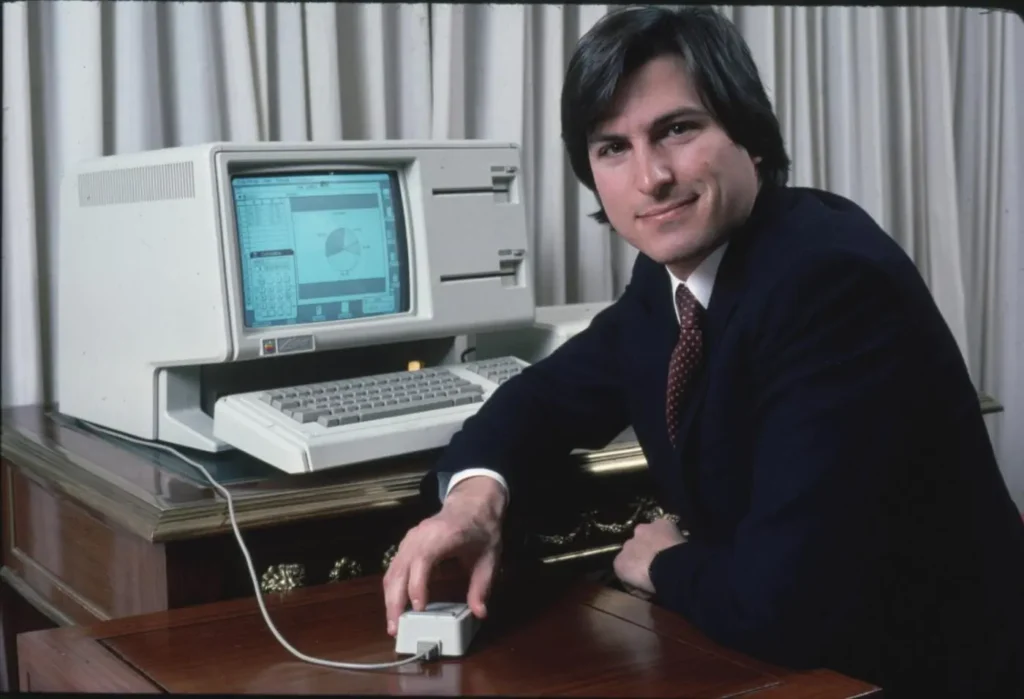

He was shown something called a graphical user interface — a computer screen where the user didn’t type commands, but rather pointed and clicked. There were windows, folders, and icons. And it was all controlled by a small device called a mouse.

Jobs watched, mesmerized, as an engineer navigated the screen without typing a single line of code. In that instant, he saw something far more profound than a useful tool. He saw the future.

Later, Jobs would recall the moment with a kind of reverent disbelief. “It was like a veil being lifted,” he said. “It was obvious to me that this was the way all computers would work someday.”

At the time, almost no one in the tech world was thinking about computers as everyday objects for ordinary people. They were seen as machines for scientists, businesses, and governments. Xerox PARC had the technology to change that — but not the instincts. Jobs had no hand in inventing what he saw that day. But he left the building knowing it would become the centerpiece of Apple’s next machine: the Macintosh.

So here’s a question worth asking: What if Steve Jobs’s true talent wasn’t invention at all, but recognition? And what if his success wasn’t just about brilliance, but about something more… circumstantial?

What Makes Success?

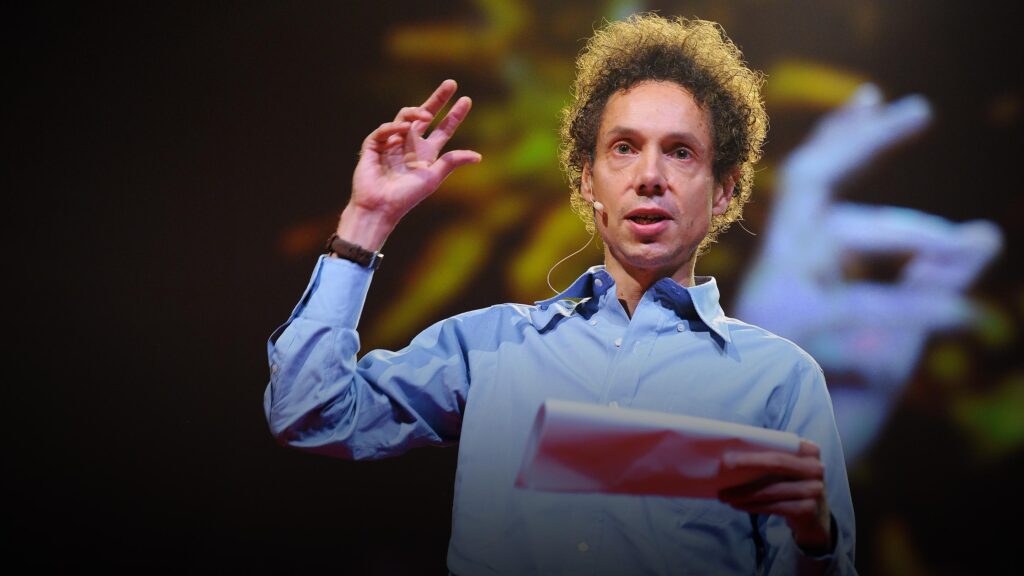

In Outliers, Malcolm Gladwell argues that we misunderstand success. We think it’s about talent and determination — internal qualities. But what if it’s also about timing, privilege, practice, and culture?

Jobs’s story, when seen through that lens, becomes more complex. And more interesting.

Let’s start with timing.

The Decade You Were Born

Jobs was born in 1955. At first, that seems like a boring fact. But as Gladwell points out, being born in the mid-50s placed him in a unique sweet spot. He came of age just as personal computing was becoming viable. Had he been born 10 years earlier, he might have been too entrenched in the mainframe world. Ten years later, and he might have missed the wave entirely.

He wasn’t the only one. Bill Gates was born in 1955. So was Paul Allen. Eric Schmidt? 1955. It’s almost eerie. A cluster of future tech titans, all born within a year of each other. Coincidence? Maybe. But more likely, a generational advantage — a birthdate that positioned them perfectly for the PC revolution.

So, was Jobs brilliant? Certainly. But would brilliance alone have been enough if he’d been born in 1940? Or in 1970?

The Magic of 10,000 Hours

Then there’s practice.

Gladwell’s 10,000-hour rule is often misunderstood. It doesn’t mean that anyone can be great at anything with 10,000 hours of work. It means that even the most talented people need immense time and opportunity to hone their skills.

Jobs had access. He had early exposure to electronics through his father. He tinkered with circuits, took apart radios. Later, he had access to a computer terminal at Reed College and immersed himself in the countercultural ethos of California — which, incidentally, helped him see computers not as cold business machines but as tools for human expression.

He wasn’t practicing randomly — he was practicing in the right domain, surrounded by the right tools, at the right time. Not everyone had that luxury.

Would he have logged 10,000 hours in electronics if he’d grown up in a rural town without a tech scene? If he hadn’t met Steve Wozniak? If he hadn’t grown up in Silicon Valley?

Cultural Legacies Matter

Gladwell also talks about cultural legacies — patterns we inherit from the societies we grow up in that shape our behavior in subtle ways.

Jobs was the child of the Bay Area — a place shaped by the counterculture, by an obsession with design, by an embrace of the new. He was adopted by a family that valued tinkering and craftsmanship. He went to an alternative college and took calligraphy classes, of all things — a decision that later inspired the typography of the Mac.

Is it any wonder that Apple’s DNA mixed technology with design, logic with aesthetics? Jobs didn’t pluck that vision out of thin air. He absorbed it from his environment — one that quietly whispered that art and engineering didn’t have to be opposites.

Opportunity Looks a Lot Like Luck

And then there’s opportunity.

Jobs didn’t discover the GUI. Xerox did. But Xerox didn’t realize what they had. Or maybe they just couldn’t imagine the right story around it. When they showed it to Jobs, he saw its potential instantly.

That moment — often overlooked — wasn’t just about vision. It was about access. Xerox didn’t let just anyone into PARC. Jobs was invited because Apple was already making waves. He had a platform. He had a team. He had the means to take what he saw and do something with it.

The lesson isn’t that Jobs wasn’t talented. He clearly was. But so were the people at Xerox. And they faded into the background, while Jobs ascended into myth.

Why?

Because he was standing at the intersection of preparation and luck — and he knew he was standing there.

So, What’s the Takeaway?

Maybe the self-made man doesn’t really exist.

Or, at the very least, he’s not as self-made as we like to believe. Behind every story of individual brilliance is a web of advantages: the year someone was born, the tools they had access to, the mentors who helped them, the communities that shaped their thinking.

Steve Jobs didn’t build the future out of thin air. He recognized it in a Xerox lab and convinced the world it was beautiful.

So what should we really admire?

Maybe not the myth of the lone genius — but the much harder, more nuanced ability to see potential where others don’t… and to be ready when lightning strikes.

Because, as Gladwell might say, success is never just about the person. It’s about the world that made them possible.